PLAY AND THE SPIRITUAL LIFE

By Sister Ioanna (deVyver), M.Th., M.A., Ph.D.

For well-formatted 7-page printable PDF file, click here

It might be said that in many ways play is one of the most fundamental spiritual activities — or, we might say, human activities. We could add that perhaps play is actually essential to real, authentic human (i.e. spiritual) existence. We might even go so far as to contend that “To be is to play; to play is to be.” As strange as such contentions might appear from a narrow, puritanical perspective, where “play” is trite or frivolous, we contend that at least for anyone who seeks personal growth, or who wishes to pursue the spiritual path, or who desires to maximize his/her own humanness, it is vital to examine the nature and significance of play, and its potential role in our lives, especially since play is so rarely explored as something of spiritual value and worthy of serious attention.*

(* This study is a self-conscious internalization and working with the ideas of four major works. Johann Huizinga’s Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play Element in Culture (Boston: Beacon Press, 1950), and Hugo Rahner’s Man at Play (Boston: Herder and Herder, 1972) are the two pivotal studies of play and culture, and E.O. James’ Christian Myth and Ritual (London: John Murray, 1933) is extremely valuable for providing examples of how elements of play, as discussed by the first two authors, are manifested in Christian and pre-Christian ritual. Finally, this essay has attempted to correlate the ideas of Huizinga, Rahner and James to Jungian psychology, especially as expressed by the Jungian psychologist, Erich Neumann, in his Origins and History of Consciousness (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1954).)

An inquiry into the concept of play is by no means simple, as we shall see. Whereas play is something that everyone does, to correlate all the manifold manifestations of play into a logically cohesive and coherent statement of the nature and significance of play — the purpose of this essay — is an extraordinarily complex task indeed. This inquiry is an attempt to find a way through a veritable labyrinth. To a great extent, the basis of the labyrinth is the fact that so many widely divergent activities are included within the concept of play, from the obvious games and spontaneous play of children and young animals, to sacred rituals, lawsuits, love, sex, war and boxing, to poetry, symphonies, dancing and painting, to the games that people play with each other. Creation of beauty and any type of creativity are highly sublime aspects or types of play, as are “marching to the beat of a different drummer,” and “thinking outside the box.” We must ask, what does a war have in common with a Mozart piano concerto, with the celebration of the Holy Eucharist, or with a child playing in the snow? Whereas they all do share certain characteristics of play, singling out just one category of play cannot begin to adequately account for and explain the variety of possible forms of play. **

** Re: "VOCATION": This poetic meditation and the other in this essay, are by the author. To read additional such poetic meditations, see the pull-down sections "Meditations 1" and "Meditations 2" at https://stinnocentmonastery.org.

Some Common Elements of Play

Let us endeavor to define some of the common elements of play. Play may be defined as a stepping outside of ‘ordinary’ life into a temporary interlude, an in-between realm, frequently bound closely by time and space, and by accepted rules. Play, by definition, may be said to be superfluous, for it is outside the sphere of necessity or material utility. Play belongs to a sphere characterized by a play-mood of enthusiasm and even ecstasy, love, and absorption into the play-world, where we temporarily become another being, existing in another realm — a realm of order, rhythm and harmony, but also at times, a realm of tension, competition and death. Play is frequently a contest or competition, which is usually performed in a specially-designated and marked-out space, a play-space isolated from the rest of the world, be it the separated space of a chessboard, playground, theater, courthouse, sports arena, church or sacred temple and altar.

Besides the special separated time, space, mood, rules and order, special clothes are frequently used — such as vestments and robes, uniforms, costumes, disguises — plus special paraphernalia — such as the wide range of sporting goods and game equipment, instruments and tools of all sorts, the different material components of the arts and the sacraments, or simply the body, the vocal chords and the mind.

Of all these various and sundry characteristics that are involved in a definition of play, it is apparent that they are not all equally appropriate to all types of play. For instance, there is a certain type of play, epitomized by the play of children and young animals, where one’s play is unplanned, unstructured, free and spontaneous, limited mainly by the boundaries of the human body, mind and imagination, and the physical environment. It is not difficult to recognize this childlike type of play as an external and visible expression of the inner and invisible state of being, reflecting a certain childlike simplicity, openness, innocence and trust, without any thought of manipulating any thing or any one, or showing oneself as superior in any way — but simply rejoicing in the sheer joy of being. The elements of this kind of play are almost the antithesis of the general definition of play (such as Huizinga proposes in his Homo Ludens). Furthermore, however, I suggest that this childlike play, when freely chosen as an adult, after one has become aware of the alternatives, must be quite close to what is meant by “except you become as little children, you cannot enter the Kingdom of Heaven.” Such an understanding of play and its significance is not, in general, adequately comprehended, as is reflected even in Huizinga’s own concept of play, which we suggest is therefore incomplete. It is contended here that Huizinga incorrectly over stresses competition and contest as the primary play elements, with its accompanying need to prove one’s superiority.

It seems that all the numerous facets of play might be better accounted for and comprehended if one were to consider play as a series of five stages, corresponding to five stages of individual emotional/spiritual growth and development, which might be perceived and analyzed behind the play-forms. Participation in the play-forms helps the individual (and group) progress through each stage of development, if growth is not fixated at one spot (which, we suggest, is, indeed, widespread).

Five Stages of Development

In the first stage of development, the baby-stage, we see that a baby’s play is very self-oriented: others may play with the baby, but it is basically oriented towards the baby. As a baby grows, much of its play focuses on marveling at and exploring the world around him, and gradually the amount of play based on interacting with others increases, as does his imitation of the roles of others. In early pre-school years, there is virtually no separation or distinction between the realm of play and the ‘real’ world — existence is not yet divided for him, as it will become in the second stage of development.

In the second stage of development, the child-stage, we find that after a number of years, a child starts to become capable of play based on the divisions into opposite teams or sides. By the ages of seven and eight (the second and third grades), much of a child’s play is comprised of games based on these divisions — various sports and games of physical dexterity and coordination, plus table-top type of games of mental dexterity and chance. In this second level of play, there is reflected the psychological-spiritual development of the awareness and distinction of opposites — of boy/girl, good/bad, fair/unfair, man/woman, play/not-play, and ‘us’/‘them.’ Most of the play of children involves the awareness of this division of the world into opposites, and the consequent tension between these opposites.

This tension continues into the adolescent years, and the third level/stage of play. Whereas in the second level of play, that of children (except for those who are emotionally disturbed), there does not seem to exist the element of violence for the sake of violence, nor the sense of enjoyment in the systematic acts of injury, mutilation or killing of animals and humans that appears in the third stage. Although basically normal children are sometimes cruel to animals and other children, it is generally an immediate expression of hostilities, and not a matter of pre-planned ‘fun and games.’ However, in the third stage of development and its corresponding category of play, the adolescent level/stage, we find that organized, socially approved, encouraged or even enforced violence, fighting and killing, is the basis of the play, as is characterized by hunting ‘for sport,’ boxing and wrestling, war and the military, and other such organized activities where even sadism and masochism can be quite prominent. Related to a lesser degree would be big-time football, blood and guts violence in movies and TV, and also play where one takes on life and death, win or lose risks, such as race-car driving or very high-stakes gambling. It would seem only logical that this type of play, like most other behavior, is the outward reflection of the inner psychological state. This third level of play, we contend, reflects the inner stage of consciousness and growth where the person has not yet been able to recognize and face within himself the existence of destructive forces threatening to engulf and destroy one’s own ego, self and identity. Thus, the violent fight between life and death within oneself is externalized into one’s life, especially into the play-sphere, where one continually needs to prove oneself superior. This violent struggle between one’s acceptable and ‘good’ higher self, and the suffocating, destroying aspects of one’s lower self is characteristic of the adolescent stage of consciousness. We suggest that our culture as a whole is fixated at this stage, and its manifestations are everywhere apparent in daily life and the “news.”

However, there is additionally a fourth stage of development and play, the adult or mature stage, which is the theme of so many myths and folk tales, wherein the individual begins — always with divine or supernatural help in these myths and tales — to face, accept, and overcome these opposing elements within oneself (typically by overcoming some external evil or challenge), and thereby to move on towards achieving transformation. We see once again the parallel between the level of play and the level of spiritual/psychological growth and development. In this fourth stage of development, the stage of overcoming one’s inner conflicts and claiming one’s true self, there is still the strong element of contest, testing and proving, but it is not blindly thrashing about as with the third level of play/development, but is a concerted effort towards a goal — to gain the treasure, the prize, which is one’s own self. In psychological terms, the treasure is the opposite component of oneself — Jung’s animus or anima — with which one is reconciled and wedded to, living “happily ever after.” This level of play is dominated not by violence, but by the studied effort to prove oneself worthy of the prize — usually by means of play’s intellectual, athletic, artistic, or other expressions. Much of the best of classic folk tales and myths, literature and modern drama and film, (of which the Star Wars, Indiana Jones and Chronicles of Narnia trilogies are superb examples), express these universal themes of struggle between higher and lower inner selves.

When the hero has overcome all obstacles, killed the dragon, and claimed the fair young maiden as his bride, the move is then made to the fifth and final level of play and consciousness, the stage of transformation and unification, where the fearsome opposing components of oneself are reconciled, and the creative play of rhythmic ordering of movement in time and space, and beyond time and space, are the visible results. At this, the highest stage of play, the elements of contest, competition, violence and the continual need to prove one’s self-worth and superiority are minimal. Instead, order is brought out of the former chaos and conflict, and the rhythm of the reconciliation, harmonization, and balancing of opposing elements are the visible components of the play forms. At this level of play, a person can create and rejoice in creation out of sheer delight and abandonment, because the person has been victorious and won the prize of his creative, unified self. This is the theme of all religion, and the goal of the spiritual quest. Music, dance, poetry, the visual and literary arts, and all pursuit of beauty are the play-forms most capable of soaring to the heights of this highest plane of play and spiritual existence.

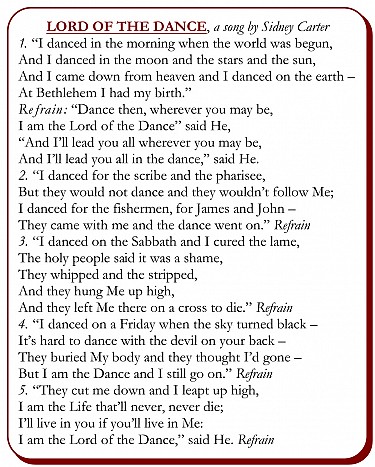

To attain this stage of consciousness and its corresponding play-forms, is experienced by the individual as a death and rebirth, but it is also an event that has to be frequently relived and re-presented, for just as at any prior stage one can get ‘stuck in a rut,’ so too, this new birth has to be re-experienced and thus kept new and vital. This is the theme and purpose of all sacred play — death and rebirth, repeated and revitalized. In the sacred rituals, the ideal and goal of all existence is proclaimed to be resurrection into a new realm of existence where the conflict and tension of opposites has been overcome and reconciled in victory. This is the message of the Christian Gospel, that Christ — the ‘Lord of the Dance’ (see Sidney Carter’s song, “Lord of the Dance”) — shows the way to be imitated, the way of the play and game of new resurrected and transfigured life in God. This is the theme of the Church’s Sacraments/ Mysteries. This is the theme of the prototypes of the Church’s Sacraments, the archetypal coronation rituals, royal and celestial weddings, new year’s festivals, and other expressions of sacred play, such as processions, ritual games which are contests between the powers of life and death, sacred dramas, and many specific games and rites associated with specific seasonal feasts and celebrations. From the earliest times, the ritual theme of life, death and rebirth on a cosmic level, has been regarded as corresponding to the human process of growth, whereby individuals or groups view their death and resurrection as a participation in the cosmic pattern, perceived in the daily rhythm of rising, setting, and rising again of the sun; in the stars’ and moon’s cyclical life; in the seasons, labors and zodiac symbols of the months; and in the growth cycle of the crops and vegetation upon which life depends. (A visual expression of these themes is frequently found in the small sculptures of the symbols of the 12 months and their seasonal labors, and the 12 zodiac signs, surrounding the portals of many Western European medieval churches, representing the cosmic nature of the sacred space and sacred drama one is about to encounter as one enters through the portals.) Consequently, the visible element used to set apart the sacred space wherein the cosmic-divine-human drama of death and resurrection and salvation-history is enacted and participated in, is the cosmic canopy of heaven.

The Cosmic Canopy of Heaven

The source of all love and beautyThis cosmic canopy of heaven, in its many forms, signifies that the actions enacted beneath or before it assume the nature of both microcosm and macrocosm. As microcosm, the sacred play ritual under the cosmic canopy brings to earth the reality of the cosmic rhythm of death and transfiguration/ resurrection. As macrocosm, the cosmic canopy symbol affirms that participation in its sacred play rituals of death and resurrection is extended and projected out and assumes the nature of cosmic reality for its participants. This cosmic canopy, in its numerous forms, we designate as the skēnē (pronounced skee-nee). The use of this Greek word is derived from its use in the Septuagint (the Greek translation of the Hebrew Old Testament) to translate several Hebrew words for the Tent and Tabernacle of Moses. In both the Septuagint and the Greek New Testament, whenever the word skēnē is used, there is the association of a place where God’s Presence (Shekhinah) resides. Forms of the skēnē include the dome, canopy, iconostasis, tabernacle, niche, triumphal arch, various types of portals, and other gabled or curved horizontal forms, supported by two or four pillars. All forms of the skēnē signify and set apart a sacred playground where sacred play rituals are enacted, wherein a theophany has occurred at sometime in the past, or where it is hoped or expected that the Divine Presence will manifest itself as a result of the play rituals.***

(*** For further consideration of the symbolic meaning of the skēnē, see the author’s doctoral dissertation: The Skēnē— a Universal Symbol of the Divine Presence: Perspectives on the Form and Function of a Symbol [Michigan State University, East Lansing, 1982].)

The Spectator of Play

A common feature of play is the spectator, be it at a sports event, a ‘play,’ a concert, or a sacred ritual. If the spectator is caught up in the play-mood of the happening, he participates in it and appropriates the effect of the play for himself. If the spectator does not enter into the spirit of the play, he is usually bored and finds the play-form dull and even a waste of time. Yet, if the play act is regarded as something to which one might aspire as an ideal, to which one is drawn, even if with some ambivalence, one may yet honestly be a spectator of the play of others, while not totally joining in. An example is someone who wishes to learn the play-language and rules of a game and thereby grow to appreciate the play-form and participate in it more fully. Thus the play can become a means of growth as well as an expression of where one already is. Further examples are attending a concert, or going to a museum, or attending the Liturgy of the Church, as something one wishes to grow into and learn to appreciate more. We can see here how the same play-form may be experienced at a variety of levels by the spectator, just as one might approach a swimming, soccer, or other competition simply to enjoy the game, whether one excels or not, or one might approach it as a life and death judgment of one’s own self-worth.

The Five Levels of Play are Fluid

A further consideration of play is that the five levels of play which we presented as being the visible manifestation of the five inner stages of growth of consciousness and spirituality, as well as being the indispensable means of achieving that growth, are fluid to a certain extent, particularly between one stage and the ones bordering on it. People frequently slide around from one to another, especially towards the lower level from which one has grown, particularly as a means of relaxation from work or stress or illness. The artist or scholar might well relax by playing a competitive game or sport, but one’s attitude and approach towards the relative importance of the playing and winning can vary considerably, as mentioned above.

Play as a State of Being

Thus far, we have attempted to define a working hypothesis of play, not only as an outwardly observable activity to be considered sociologically, anthropologically, psychologically and theologically, but as the exterior and visible component of the interior and invisible state of being, and as a means of growth towards perfection (deification or theosis).

We would now like to inquire further about play as a state of being. It is contended that play is not just an activity and a means of growth, but a desirable goal to work towards achieving as a state of being — not just an activity, but a way of approaching all activities, a way of being-in-the-world. In this way, the antithesis of play is not work or seriousness — for one can approach one’s work playfully, and one’s play seriously— but perhaps despair and gravity or weightiness of soul is the opposite of playfulness as a way of being, a state of being. To approach all of life playfully, with a playful spirit, yet being aware of life’s seriousness and demands and its meaningfulness, seems to be a way of not only expressing the inner state of being corresponding to the fifth and highest level of play, but also expressing the goal of the Christian vocation and spiritual journey. Hugo Rahner, in Man at Play quotes widely from Patristic sources and non-Christian philosophers of the pre-Christian and early-Christian eras in numerous passages where they talk of the play and dance of God, of the Logos, of the Holy Spirit, of the Church, of the cosmos, and of man, whereby he participates in and imitates the image and likeness of God, and the dance of the celestial spheres. Herein is the root of what we could call a “theology of play” (and a theology of beauty also, that is so fundamental to Eastern Orthodox theology and spirituality).

Although one of the elements in a definition of play is that play is an end in itself, which has its own intrinsic value, yet there is a way in which play may also be said to have a function outside itself. While engaged in the play-acts, when one is indeed caught up in its play-mood, ends other than the play itself are irrelevant— the mind is boggled and nothing else matters while under play’s spell-binding influence and total concentration, whether that spell includes winning at all costs, or entering into the heavenly dance, its rhythm and music. Yet play also serves the function of expressing the higher stages of perfection and transfiguration, by means of participating in the higher levels of play before we have made the quantum leap to the higher level. First, we repeatedly act out in play the successive stages of our growth, both attained and yet to come, as we slowly appropriate our play-acting as our own education in play and growth. Thus there is an indispensable purpose and function of play outside the enjoyment of the play itself. Plotinus said that “all play....arises from the longing for the vision of the divine” (Rahner, p. 65).

What is the ‘Real’ World?

There remains one final question to be asked here — what is the ‘real’ world? One major element in any definition of play is that play steps outside the ‘real’ world into a ‘pretend’ or ‘make-believe’ world. But maybe these terms are reversed, and maybe the sphere of play is the real world of ultimate importance and significance, and the day-to-day humdrum ordinary existence is the world of pretend that is of lesser or even of little importance. It was mentioned above that in the play of the child there is no dichotomy whatsoever between play and the for-real, for in the oroboric**** existence of the infant, reality is one and undivided.

(**** The oroboros (also, ouroboros) is an ancient symbol depicting a serpent, snake or dragon biting its own tail. Snakes are universal symbols of rebirth, transformation, immortality, and healing, (partly because it sheds its own skin). Thus, the oroboros is often seen as a symbol for eternal cyclic renewal or a cycle of life, death, and rebirth.)

Then, the original unity is broken, one’s original innocence lost, and everything becomes bifurcated into opposites, (mythologically referred to as the separation of the World-Parents or ‘The Fall’), including the split between the so-called ‘real’ world and the ‘make-believe’ world. This separation we can accept readily enough in the external world around us, but it is a far more threatening condition to find within oneself — such a reality is too threatening to be accepted at lower stages of development, so one retreats into the ‘comfort’ and ‘security’ of daily existence, reversing the terms and calling this daily existence the ‘real’ world. In play, the divisions of existence are ever before us, along with seeking to enact the victory within onself, then the parading of such things is relegated to the make-believe of play. However, as one grows towards transformation and reconciliation (i.e. salvation) and the victory over the dichotomies of existence, where the negative, destructive elements become conquered, then the radical divisions between play and the rest of life likewise begin to break down along with the other polarities. One is aware of them, yet they are in balance. If it is in play whereby the struggles and development of the person are enacted visually and corporally, perhaps then, that is the externalization of the real world where one lives. And attending to the daily necessities of food, clothing, shelter, and their procurement, preparation and maintenance, and usually the job that provides the means of procurement — perhaps this is the pretend world wherein we lose ourselves and insulate ourselves from the more important and real concerns of existence, encountered in the play-sphere that corresponds to the inner stages and struggles of growth.

The Play and the ‘Real’ Worlds Reconciled

Yet let us take this question of play and reality a further step into the highest level of play and spiritual development, where the dichotomies of existence have been conquered and have become reconciled in harmony, thus releasing the constructive energies of creation and balance. Certainly then, the dichotomy of play vs. ‘real’ world is likewise reconciled, as manifested in the playful approach to all existence, where, like the baby and young child, there is no functional difference between play and the rest of one’s life, for the real world of play penetrates all of one’s life. But here, unlike the child, one is aware of the alternatives and the dialectical tension and paradoxical nature of existence. Yet here once again is the description of the ideal — the perfection — towards which the Christian vocation and the human vocation aspire. Herein is the description of the transformed and renewed life, where one’s entire existence is given over to the most serious work of love and joining in the game and dance of existence — singing and dancing and rejoicing with David and all the friends of God and the whole company of heaven before the face of the Lord.

Praise the Lord! Sing to the Lord a new song, His praise in the assembly of the faithful!

Let them praise His name with dancing; let them sing praises to Him with timbrel and harp!

(Psalm 149:1,3)

St. Innocent of Alaska Orthodox Monastic Community; https://stinnocentmonastery.org; November 21, 2020