ICONS: GLIMPSES OF BEAUTY AND TRUTH

By Sister Ioanna (deVyver), M.Th., M.A., Ph. D.

St. Innocent of Alaska Monastic Community, Redford, Michigan

For an 9-page PDF file, click here

Why is Beauty Important?

Beauty is important for Orthodox Christians because it reflects the Divine Nature. The beauty of icons is an important vehicle for apprehending the Divine. Icons are glimpses of the Beauty and Truth of what is ultimately Real in life, and consequently, they help us to know our own true selves. Furthermore, icons are not just “nice,” they are absolutely essential for Orthodoxy, because they proclaim and affirm the same Beauty and Truth of salvation-history as the Gospels and the cross reveal. In short, icons teach us:

* who God is,

* who we are,

* how we are to live, and

* the purpose and meaning of life.

In the following, we will attempt to make these concepts clearer.

Beauty as the Path to God

What is the essential purpose of our even discussing the nature and meaning of icons? Hopefully, it is because we are, or wish to be, “friends of God.” Plato tells us in his Dialogue, Symposium, that Beauty is the path to God, and being “friends of God” is the ultimate goal. He basically says that the lover of beauty is a lover of virtue and good, and that the love of material beauty leads up a ladder or hierarchy of beauties, until we perceive the absolute and true Beauty — the divine Beauty Itself. Contemplation of that true Beauty — simple and divine — is the highest human activity, Plato contends. This platonic “vision of Beauty” has had a profound effect on the Orthodox theology of beauty and of the icon.

As aspiring “friends of God,” therefore, assumedly, we are also lovers of beauty. Since virtually everyone intuitively loves beauty, this suggests, indeed, that everyone is naturally attracted to God. But that natural attraction gets thwarted so readily, that it frequently doesn’t get past the material sphere. For Orthodox Christians, that natural attraction to beauty receives the fullest possible development and satisfaction in its icons and liturgical music (both basic components of the liturgical life of the Church), and in the architectural setting (like a stage-set) within which the liturgical dramas are enacted.

For the Orthodox, beauty is so extremely important precisely because it reflects the divine Nature, and to create beauty is to imitate the divine Activity: herein lies a fundamental element of the theology of beauty. Furthermore, since the physical church building represents the Kingdom of God, where heaven and earth meet and where God meets us, it is only fitting for that Temple of God’s Presence to radiate as much of the divine Beauty as possible. Thus, Orthodox churches should be as beautiful as possible, and are customarily adorned with icons everywhere, usually on every wall and ceiling space.

As Plato indicates, the love of beauty in the material sphere should lead to the love of the Ultimate Beauty — God Himself. Hence, whereas icons, church architecture, and liturgical music are valuable vehicles for apprehending God, it must be made perfectly explicit that they are not ends in themselves, but are only instruments, aids, or vehicles (just as the Bible and cross are) to approaching God, and becoming “friends of God.” Icons, the Bible and the cross all proclaim the same thing — salvation-history: that God comes to us to reconcile Himself with us, and to restore us to full communion with Him. It is that simple. Yet so incredibly complex! This reconciliation and communion is one of the major themes throughout the Old and New Testaments. The cross is a visual symbol of that restored cosmos — of the union of heaven and earth (the vertical bar) and the reconciliation of all creation, including humans, with itself (the horizontal bar).

Salvation-History

In the Bible we hear salvation-history proclaimed; in the liturgical life we enact salvation-history, both proclaiming it as well as making it a present event; in the icon we see salvation-history proclaimed. Hearing salvation-history proclaimed is common to all Christians and Jews. Enacting salvation history is more a part of Orthodox, Roman Catholic and Jewish practice than of most Protestant denominations. However, seeing salvation-history proclaimed in the icon is distinctive to only the Orthodox, (although others sometimes appreciate icons and might even use them). In proclaiming salvation-history, icons utilize a visual language that is perfectly clear, once we learn to recognize and understand the language.

UNDERSTANDING THE LANGUAGE OF ICONS

Let us now explore a few of the most important of the hundreds of different elements of the language of icons. In doing so, we will focus our attention primarily on four major icons: The Holy Trinity, The Annunciation, The Transfiguration and the Resurrection.

1. The Use of Gold Backgrounds in Icons. Icons are fundamentally glimpses into the Kingdom of God. One technique frequently used to convey this truth is the use of a gold background (or a simulation of gold), to communicate that this vision is not something out of ordinary life in the material realm, but is a divine vision, as in this icon that is itself an envisioning of St. John Climacus’ famous book, called The Ladder.

2. The Use of Reversed Perspective in Icons. As glimpses into the Kingdom of God, icons therefore enable us to have glimpses of the Beauty and Truth of what is ultimately Real, that is, where we encounter and perceive ultimate Reality and Truth. Iconographic language enables this to occur in many ways, one of which is called “reversed perspective.” Icons are frequently called “windows” into heaven (or the Kingdom of God). But who does the looking through a window? Indeed, we can be on the outside of a building looking in through a window, or we can be on the inside looking out. It is important to recognize that since the time of the Western Renaissance (14th - 16th centuries), it has been us who have been doing the looking at paintings. Thus, we have become accustomed to looking at paintings and other flat, two-dimensional images that are made to imitate a third dimension through the use of perspective. This use of perspective seeks to imitate how we customarily see things with our outward, physical eyes — things get smaller as they recede away from us, like railroad tracks angling towards each other as they recede into the pictorial distance. But this is purposefully very ego-centric, reflecting the Humanism of society in general since the Renaissance. It makes the theological and philosophical statement that we are the ones who determine and create Reality, indeed a relativistic attitude that we inherit today from the Renaissance and subsequent periods, and which has been become even more widespread by the current so-called “Post-Modernist” ideology.

On the other hand, it is possible for someone to be on one side of a window looking at us, whether or not we see them or are even aware of them. This is the case with icons, where we are, so to speak, the ones being looked at by those on the inside of the window, which is the reverse of our usual perspective. Consequentially, authentic icons make the theological and philosophical statement that we are not the ones who determine and create Reality. Icons make a very clear statement that the opposite metaphysical view is actually the truth — that the Kingdom of God, where God is recognized as the Ultimate Reality, the Ultimate Truth, Good and Beauty, is the basis of all reality, truth, good and beauty. The iconographic technique used to demonstrate this theological and philosophical statement is what is called “reversed perspective,” where things get larger as they recede.

More about the Presentation Icon. The use of reversed perspective is clearly shown in the above icon of the Presentation or Meeting of the Lord in the Temple on the 40th day after His birth, as recorded in St. Luke’s Gospel. The Lord is being presented with the required offering, in accordance with Jewish tradition, while the Elder Simeon is meeting Him and is about to take Him in his arms. The highly stylized portrayal of the temple and the steps leading up into it get larger as they recede from the viewer (reversed perspective), which is the reverse of the way we see with our outer eyes, the imitation of which is called “Renaissance perspective.” The stylized canopy on its 4 pillars in the upper left symbolizes the holy place or sanctuary that is at the center of the Jerusalem Temple, and thus further indicates that a theophany is occurring, or a meeting between God and man. The red curtain draped across the top indicates that the event occurred inside the building. (See more about this below in the Annunciation icon.)

RUBLEV’S THE HOLY TRINITY ICON

Another example that shows “reversed perspective” is St. Andrei Rublev’s famous icon, The Holy Trinity, (dating from approximately 1423), where we see the two thrones and footstools getting larger as they recede. The overall composition enhances this perspective by being narrow at the bottom (at the feet), angled diagonally up and out so that the fullness of the composition is not at the front, but at the rear of the pictorial space.

Sometimes people mistake the non-illusionistic use of perspective as lack of knowledge of how to paint “properly.” However, Rublev demonstrates that he does know how to use Renaissance illusionistic perspective in his treatment of the peculiar rectangular inset into the front of the altar-table, immediately under the chalice with the Eucharistic Lamb. We can only speculate about why he included this unusual inset. In the context of our present considerations, however, it might be regarded as a symbolic reminder that windows are used in two ways. Whereas the icon itself is a vision of Reality “looking out” at us, the peculiar inset might remind us that we are also there “looking in,” occasionally getting glimpses of Ultimate Reality, rather like looking at a ball-game through a tiny hole in the fence?

3. The Use of Light in Icons

To mention another element of the extensive iconographic language utilized in this Holy Trinity icon, we notice that there are no shadows; there is no external source of light; everything is illumined equally. This stylistic device conveys the meaning that nothing dark, evil, or negative can exist in the Presence of God and that the Light of Divine Being illumines all. (Black is properly employed only to represent the rejection of God’s Presence.) It is also another way of proclaiming that this is a vision of Divine Reality, where, as we are told in the Apocalypse/Revelation of St. John the Theologian, there is no need for any outside light, because God’s Light illumines all. This is also proclaimed liturgically at various times, such as in the Presanctified Liturgy and at midnight on Pascha. The manifestation of God as Light is a very widely used universal symbol of God and His Presence, because nothing can exist without light, and the portrayal of God as Light proclaims that He is the source of all life, and Jesus, the Logos, is the Light of the world.

4. The Use of Color in Icons

Most of the time the use of color in icons is somewhat muted and a small palette of colors is used, as we see in the Rublev Holy Trinity icon. This lends a feeling or tone of peace, quiet and tranquility, characteristic of being in the Presence of God in His Kingdom. The use of color is also distinctive here to correspond to and convey the fundamental theology of the Holy Trinity. In this Old Testament vision of the three angels who appeared to Abraham by his house by the oak of Mamre, that is understood as a prototype of the revelation of the Holy Trinity, the angel on the left represents God the Father. Thus, His outer garment is almost invisible; it almost has no distinct earthly color, and is almost transparent, showing that He is invisible to earthly eyes. The central angel represents God the Son, Jesus Christ, Who did manifest Himself in earthly form as a man. Therefore, His inner garment is a solid, earthly brownish color. And the angel on the right represents God the Holy Spirit, Who is the sustainer of life. Therefore His outer garment is a semi-translucent green, translucent, because like the wind and breath, the Spirit is invisible, but we see His effects (the word for Spirit is the same as both breath and wind in Hebrew, Greek and Russian); and because green represents life, as we rejoice in the Spring when the deadness of winter becomes alive again and everything turns green. (This is expressed on the Feast of Pentecost, the Descent of the Holy Spirit, when traditionally, green plants, trees and branches are used to decorate Orthodox church temples.) Furthermore, in this Holy Trinity icon, St. Andrei Rublev expresses the vital Trinitarian theology that while each Person of the Holy Trinity is separate and different, they share one Nature/Essence/Substance (ousía). He conveys this by the use of the same blue color in the inner or outer garments of each of the three angels.

5. The Use of Composition in Icons

Composition is a further means of proclaiming the theology of the Holy Trinity. St. Andrei uses a circular composition to show the unity of the three Persons of the Holy Trinity, whereas the heads of the two angels that represent God the Son and the Holy Spirit are tilted towards the angel representing God the Father, to show that the Son is begotten of the Father and the Spirit proceeds from the Father. The angel representing God the Father, sits upright, unmoved and in total calm. Barely visible behind the three angels in this six-hundred-year-old icon, and that correspond to the historical prototypical Old Testament event are: Abraham’s house behind God the Father, representing the mansion of the Father of all; the Oak of Mamre near Abraham’s house, symbolizing the tree of the cross on which the Son will be crucified; and a mountain, which is a universal symbol of the theophany and meeting of God and man, as well as a symbol of the expansive creation that is life, of which the Holy Spirit is the giver, preserver and sustainer. The faces of each of the tree angels are virtually the same, again showing the theology that the three Persons of the Holy Trinity, while separate, are also One and undivided.

THE ANNUNCIATION ICON

A third example of “reversed perspective” is a sixteenth century Russian icon from Novgorod of The Annunciation. Architecture usually provides the most dramatic use of reversed perspective. Looking beyond the perspective itself, we observe in this icon a brilliant use of composition to show important theological truths, in that the architecture seen here is absurd! The proportions are illogical; the doors and windows could never be used; and the canopy over the head of the Theotokos could never stand up on its supports, one of which is over a hole in the roof. We witness in this icon the very self-conscious use of symbolic language to convey spiritual truth. According to the human perspective, the Truth and Reality of the Divine realm, which is portrayed in icons, seems contrary to (human) reason. However, to invert our perspective, we might say that it is the materialists’ concept that only the visible world is real that is to be questioned — as contrary to Divine Reason. Obviously, we have here a striking clash of values and of metaphysical systems (that is, what is really Real?). According to human reason, a virgin cannot give birth; the Invisible cannot become visible; the Immaterial cannot become material; and God cannot become man. But according to Divine Reason, all these things have occurred. Thus, this seemingly paradoxical concept of Truth is expressed by the use of absurd architecture, for buildings are only made by humans, whereas people, animals and nature are made by God.

6. The Use of a Curtain Draped Across the Top of Buildings in Icons.

Another aspect of the iconographic language in this icon of The Annunciation is the curtain draped across the top of the buildings. (We also saw this above in the icon of The Presentation/Meeting of the Lord in the Temple.) This iconographic custom signifies that historically, the event depicted occurred inside a building. Why is this? The reason reflects a very vital spiritual and theological principle: authentic icons never depict events as happening inside a structure, but in front of the building (or at the mouth of a cave). This demonstrates a further example of how symbolic language is used in icons to convey fundamental spiritual concepts. God, His Truth and Reality, His Presence, cannot be confined to any one historical time and place. Depicting an event in our Salvation-History as taking place inside a building would convey that God can be confined to one specific time and place, whereas the opposite is true: His Self-revelation in salvation-history is cosmic— valid for all persons at all times and places, as in a microcosm. Furthermore, in the Kingdom of God, time, space and place are irrelevant, for they are constructs of the material realm. One of the several ways of communicating this vision of the nature of Reality is to depict events as occurring in front of draped buildings, showing that the icon has its foot in two realms: on the one hand it corresponds to a specific historical event and revelation, while on the other hand, it retains its cosmic significance.

7. The Essential Nature and Purpose of Icons

Let us step back for a moment in our inquiry into how some different elements of the language of iconography provide us with glimpses of Absolute Beauty, Truth and Reality characteristic of the Kingdom of God, and explain precisely what the nature and purpose of icons are. It is essential to recognize that icons are not just “pretty and nice,” and are not simply for didactic purposes, as many incorrectly claim. Herein, in fact, lies the fundamental difference between Western religious paintings and representations, and authentic Orthodox icons. Western theologians at the time of the Emperor Charlemagne (late eighth – early-ninth centuries), during the Iconoclastic Controversy of the eighth and ninth centuries (ca. 730-843), rejected the dogmatic decisions of the Seventh Ecumenical Council of 787, and its Orthodox theology of icons. Instead Charlemagne claimed that religious art was only for the decoration of churches and for the instruction of the people, (who were mostly illiterate at that time). Most Western art historians and even some Orthodox writers have continued to perpetuate this ninth-century non-Orthodox misconception, which may be true for western religious art, but not for authentic Orthodox icons. On the contrary, the essential nature of the icon is to make present (to re-pres-ent) events and persons of salvation-history, and to affirm the Incarnation, Resurrection and Transfiguration of the cosmos that has fallen away and separated itself from its true divine nature and its life-source. The stylistic symbolic language of the authentic icon presents a vision of that Reality from which we have fallen, and to which we are called to return.

Furthermore, icons are instruments that God gives to us out of our own need to see and touch in the material realm, before we can be led beyond to see and touch in the spiritual realm. But because icons are made out of material “stuff” — wood and paint and mosaic — they declare something very significant. They proclaim that the material world, like human nature, is essentially good, because God made it good — it is fallen, tarnished, but with care, it can be restored to its original purity. This concept of human nature as good (not depraved or devoid of divine grace, as many Protestants claim), and that the material world can, does, and must participate in salvation and sanctification, is fundamental to the Orthodox theological and spiritual principles. This view is considered affirmed by the Incarnation, wherein God took on human flesh and nature in Jesus the Christ, so that we might be restored to our original image (eikon means image in Greek), in which God created us.

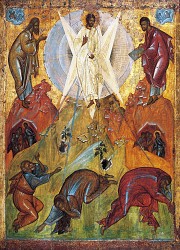

THE TRANSFIGURATION ICON BY THEOPHANES THE GREEK

But indeed, when the Mind-Soul and body become completely in harmony with itself and with God, the body does become transfigured, and radiates divine light and energy. To portray the transfigured flesh and radiant energy in paint on a panel is a most challenging task even for the best of iconographers. Theophanes the Greek, a contemporary of St. Andrei Rublev in the early 15th century, accomplished this transformation perhaps better than anyone else. His icon of The Transfiguration is one of the finest portrayals of the meaning of the Transfiguration. Christ is surrounded by a magnificent aura of glory, His clothes glistening white. The Uncreated Light of Mount Tabor radiates as brilliant white, as the gold rays on His clothes and in the glory, and as the lower vibration of the pale silvery blue that strikes the three Apostles to the ground. The Holy Prophets, Ss. Elias (Elijah) and Moses, bathed in the brilliant white light, stand just touching the outer edge of Christ’s glory, silent witnesses to this great theophany, as they previously had been witnesses to theophanies on Mt. Sinai.

The iconographic language of this icon strikingly demonstrates that spiritual growth is a long, gradual, even painful process, and that what we perceive of Truth and Reality at any particular time is all we are ready to deal with at that time. In many of the hymns for the Transfiguration we find repeated mention that the three Apostles perceived the glory of the Transfiguration only insofar as they were able to. The iconographic language declaring this important understanding is that St. James (on the right) is thrown to the ground, his back to Christ, with his hand completely covering his eyes. St. John (in the middle) is also thrown to the ground with his back to Christ, but his hand is not covering his eyes, just shielding them. St. Peter (on the left) is similarly thrown to the ground, but he is facing Christ, with his hand in front of his eyes to protect them from the overwhelming brilliance of the Glory of God — of the Uncreated Light that surrounds Christ.

The iconographic language of this icon strikingly demonstrates that spiritual growth is a long, gradual, even painful process, and that what we perceive of Truth and Reality at any particular time is all we are ready to deal with at that time. In many of the hymns for the Transfiguration we find repeated mention that the three Apostles perceived the glory of the Transfiguration only insofar as they were able to. The iconographic language declaring this important understanding is that St. James (on the right) is thrown to the ground, his back to Christ, with his hand completely covering his eyes. St. John (in the middle) is also thrown to the ground with his back to Christ, but his hand is not covering his eyes, just shielding them. St. Peter (on the left) is similarly thrown to the ground, but he is facing Christ, with his hand in front of his eyes to protect them from the overwhelming brilliance of the Glory of God — of the Uncreated Light that surrounds Christ.

In this icon we are summoned to become witnesses of Christ’s Transfiguration as a present event. The composition, colors and style of the icon summon us to acknowledge that we, along with all creation, are called to participate in the spiritual reality of the transfiguration of the material world.

The Transfiguration was the only time prior to His Resurrection that Christ appeared in glory. Just as the icon of the Transfiguration reveals what this historical biblical event and spiritual experience means for us personally, so the icon of the Resurrection does a similar thing. They both are visualizations of the meaning of the feasts themselves. They both proclaim that our essential nature is to live transfigured and resurrected lives. The Transfiguration of Christ was in many ways an anticipation of the Resurrection, and they are closely related.

THE CHORA CHURCH RESURRECTION ICON

Having discussed a few of the aspects of the meaning of the icon of the Transfiguration, let us now inquire how the iconographic language of the Resurrection icon reveals glimpses of Beauty and Truth that can mean something in our own lives.

Meaning of the Iconographic Language of The Resurrection Icon. In the late Byzantine (1320-40) fresco of The Resurrection of Christ in the Church of the Chora (also called the mosque of Kariye Djami) in Constantinople, we have an exceptionally dynamic and energy-filled vision. Christ’s stance is a major means of communicating that energy. Portraying Him with His feet apart, and His body on a diagonal, gives a sense of thrust and of power, rather like capturing all of the concentration of energy of a champion athlete at the last moment before releasing that energy in an athletic competition. The athlete’s energy is life-force energy. How appropriate then to use that imagery for Christ, as the source of the life-force energy that created the cosmos. Christ as the Creator means that Christ brings new-life into being. And that is precisely what He is doing here. We might even say that He is functioning as a mid-wife in this icon, emphasized by the distinctive shape of the glory.

Frequently in icons of the Resurrection, such as this one to the left, Christ holds a cross or scroll in one hand, while He grabs Adam’s wrist with the other, and there is less energy and more tranquility (victory has been achieved, the battle over). However, in the Chora Church fresco, Christ is depicted with both His arms outstretched, and this adds further energy to the mood of the icon. Typical of most Resurrection icons is that the dynamic energy of Christ’s Spirit-filled victory over death is enhanced by the fluttering out of Christ’s garments in the wind (which symbolizes being filled with the Holy Spirit), and even that sometimes spills over into Eve’s and Adam’s garments.

What is the meaning of these various elements of iconographic language? The most prominent statement is that Christ is quite literally dragging Adam and Eve — hence, all men and women, yea, all the cosmos — into new and resurrected life, almost against their will. We observe that Christ is grabbing their wrists, not their hands. There is considerable difference between taking someone’s hand and grabbing their wrist: the former is reciprocal; the latter is without consent or cooperation. A parent might grab a child’s wrist to force the child to do something he is resisting. When a child is physically born into this life, he resists and must be pulled out, and the process is painful. So likewise is spiritual birth painful, and therefore we resist it frantically. If it weren’t that Christ grabs us and drags us into resurrected life — with us kicking and screaming all the way — we would still be kept captives in the bonds of hades. Do we not find that spiritual growth, in any of its stages, so often seems to be the result of much pain, agony and suffering? Consequently, it is fully appropriate for this icon to use symbols of physical birth and labor to speak about spiritual birth and its labor pains. Furthermore, the power and life-energy of Christ’s athletic stance and spirit-filled clothes flapping in the “wind” are also appropriate, for they declare that by His Resurrection, Christ bestows life upon us who are in the tombs, by means of trampling down death by His own death. Let us analyze this use of symbolic language to discover what spiritual truths are conveyed.

First of all, we must recognize that it is we who are in the tombs. What does it mean to be in the tombs? We think we are alive, don’t we? How can we relate to being dead? Of course, we must realize that we have two types of life and two types of death — the physical and the spiritual. Much of the fallen cosmos in which we dwell experiences only a shadow of physical existence. It is life at war with itself. It is a fragmented, tortured, alienated life in prison chains. The vision made present in authentic Resurrection icons is that true life is to break free of our chains, and to be dragged out of our prison tombs, hence to live a reconciled life, where we are reunited with all from which we have been separated — God, ourselves, each other and nature. Then we experience peace, joy, love, harmony, balance, unity — precisely the vison that authentic icons make present through complex iconographic language.

Other Elements of the Iconographic Language of the Resurrection Icon.

In the iconographic vision of the Resurrection icon, hades is depicted as black, black (the absence of light) being the symbol for life lived as though God were absent, which is hell. Christ is trampling upon the doors of hell: “Trampling down death by death....” One of Satan’s devils is here shown tied up. And there are always the various keys, locks, bolts, hinges and other agents of alienation and separation strewn about— broken up and no longer effective. Here is a magnificent and powerful declaration that life and creation are stronger than death and destruction. Death (in this context) means separation from God. But the iconographic vision declares that Christ demolished the hold that the forces of separation, destruction and death have over us. The result is the gift of the inheritance of life. But we have to claim our inheritance.

At the top sides of the Resurrection icon are always divided mountains. Mountains always are symbols of spiritual ascent and revelation, and, being divided, they also represent the world that is separated and alienated from itself and from its True source. Christ in the center of the composition, between the divided mountains, showing that He is reconciling and reuniting the alienated world with itself and with Him. This general composition is found in a number of different icons depicting events in salvation-history. The bright, usually triple, round or elliptical shape around Christ is a visualization of His Glory, here emphasized by the golden rays emanating from Him. Adam and Eve are being raised up out of their tombs, shown as rectangular stone boxes. They are kneeling to illustrate that they are being raised up. The figures behind Adam and Eve are various holy prophets and others (they vary), whose sojourn on earth ended before Christ’s Crucifixion and who were waiting for Him in the other world. Readily identifiable among them are St. John the Baptist, who is announcing Christ to them, as he did on earth, as well as Prophets and kings David and Solomon, frequently Moses, Elijah/Elias, Isaiah, the three Holy Children, Shadrach, Mishak and Abednigo, identifiable by their little round red Babylonian-style hats.

Continuousness in Icons, Salvation and Orthodox Life.

A further dimension of the vision of authentic icons is what we might term continuousness. In the feast of the new Passover (Pascha), we pass-over with Christ from death into new life. But the Resurrection is not only an annual renewal of our Baptismal rebirth: it must be continual. We had indicated before that icons transcend earthly time and space: icons depict cosmic Reality — Divine Reality. Thus, we might say that icons, and their vision of Reality, simply are — they simply exist! Their meaning and their call to us are constant, not just once a year. We follow an annual liturgical cycle which corresponds to historical events, because we are still within history ourselves, but that cycle is never supposed to overshadow the continuousness of Divine Reality. Icons, and the liturgical life with which they are inseparably bound, are meeting places of two worlds. If we allow ourselves to be brought into their existence, we can transcend the bonds of time with them. One of the consequences of standing in two worlds simultaneously is to participate in a resurrection and transfiguration that are continuous — minute by minute, day by day. Salvation, Reconciliation, Atonement — they don’t happen just once, like an “instant-salvation,” and then we’re “saved:” there is no such thing as “once saved, always saved.” They must happen continuously, because they are states of being and aspects of a continuous relationship. St. Paul’s exhortation to pray continuously, and the Orthodox attempt to realize this goal through the use of the Jesus Prayer which becomes the prayer of the heart, are other expressions of the same principle. The entire style of authentic icons, the liturgical life and music, and the traditional Orthodox church architecture — all make similar statements about the continuousness of the Kingdom of God — a Kingdom that transcends time and space and our human perspective of reality, offering instead, glimpses of divine Reality, Beauty and Truth.

Conclusion.

In our opening paragraph, we contended that icons reveal to us (1) who we are; (2) who God is; (3) how we are to live; and (4) the purpose and meaning of life. Virtually everything that we have been discussing throughout this essay has essentially been dealing with the answers to these questions. In concluding our brief excursus into the realm of icons as “glimpses of Beauty and Truth,” let us summarize succinctly the answers that icons give to these four essential life questions.

Most emphatically must we assert and affirm that the vision that icons manifest is that only God and His Kingdom is of Ultimate Reality and importance, and is the Ultimate Truth and Beauty. Icons proclaim that our true selves, our essential nature, are akin to the spiritual vision of icons. Our real selves were originally a part of that vision of Truth, Beauty and Good, but we fell away. Consequently, however, our attraction to truth, beauty and good is an attraction to rediscover our true nature, our “roots” so-to-speak, as well as to rediscover and encounter God. On the one hand, we can only encounter God when we encounter our true selves, and on the other hand, we can only know our true selves by knowing God. The vision of the purpose of life as revealed in authentic icons is to encounter God (and ourselves), or, in other words, to return home to our native homeland — the Kingdom of God — where every creature basks in the brilliant light of the Divine Presence, and where the material world is restored to its sacramental nature of being an expression and agent of communion with God. How are we to live? Icons proclaim that we are to live a transfigured and resurrected life, where we allow ourselves gradually to become more and more At-one with God. Experiencing At-one-ment with God means being constantly closer and in fuller communion with Him, while allowing ourselves to be God’s instruments of peace, love, joy, unity, reconciliation, mercy and service to a world that worships the ugly and lies, while all the time passionately longing to discover that its real nature is to love Beauty and Truth, and to be “friends of God.” This is what icons reveal; are they not truly visions, yea, glimpses, of a transfigured and resurrected world-order, glimpses of Beauty and Truth?